Article by Lorena Zárate, originally published at Minim

There is no doubt about it: the current global pandemic offers some acute warnings and delivers several fundamental messages to our societies. First and foremost, it suddenly and simultaneously focuses our attention on the vulnerability and interdependence of life; the centrality of care and essential workers, the majority of them women and many of them migrants or from racialized groups, and the critical role of neighbourhood cohesion and the proximity of services essential to our social reproduction. Public debates on social media and countless webinars are increasingly addressing the urgent need to rethink the way we organize cities and territories, design economic activities and set up decision-making processes at different scales. Throughout these debates, cooperation and solidarity are common keywords in framing claims and proposals arising from a wide range of actors.

For decades now, social movements, communities and activists around the globe have been building practices and narratives on those very messages under the related umbrellas of the Right to the City and the New Municipalism. The fulfilment of the social function of land and property; the defence of the commons (natural, urban and cultural); the recognition and support of social, diverse and transformative economies; the radicalization of local democracy and the feminization of politics are some of the most prominent principles guiding a multitude of actions and advocacy efforts. In the present context, these contributions seem more relevant than ever, for they provide concrete clues for confronting the current emergency while at the same time pushing forward substantive transformations for the years and decades to come.

Even in times of extreme uncertainty, there are a number of important things we know —and that we should not forget. The pervasive colonial/capitalist, patriarchal and racist valuesframing the pre-pandemic world have been responsible for centuries-long criminal social injustices, exploitation and environmental destruction, making our bodies, our communities and our planet more susceptible to all kinds of risks and disasters. The pandemic shock does not affect everyone the same way, and its consequences will be widespread and longstanding for vast populations already living in vulnerable conditions. At the same time, and globally speaking, humanity has the means and the knowledge (including Indigenous and First People’s ancestral traditions along with socially-committed academic and scientific production) to provide for the wellbeing of all. Bold, courageous changes are urgently needed and certainly not impossible. Tragedy and indignation, yes, but also inspiration is all around us. Can we see it?

COVID-19, underlying inequalities and renewed tensions

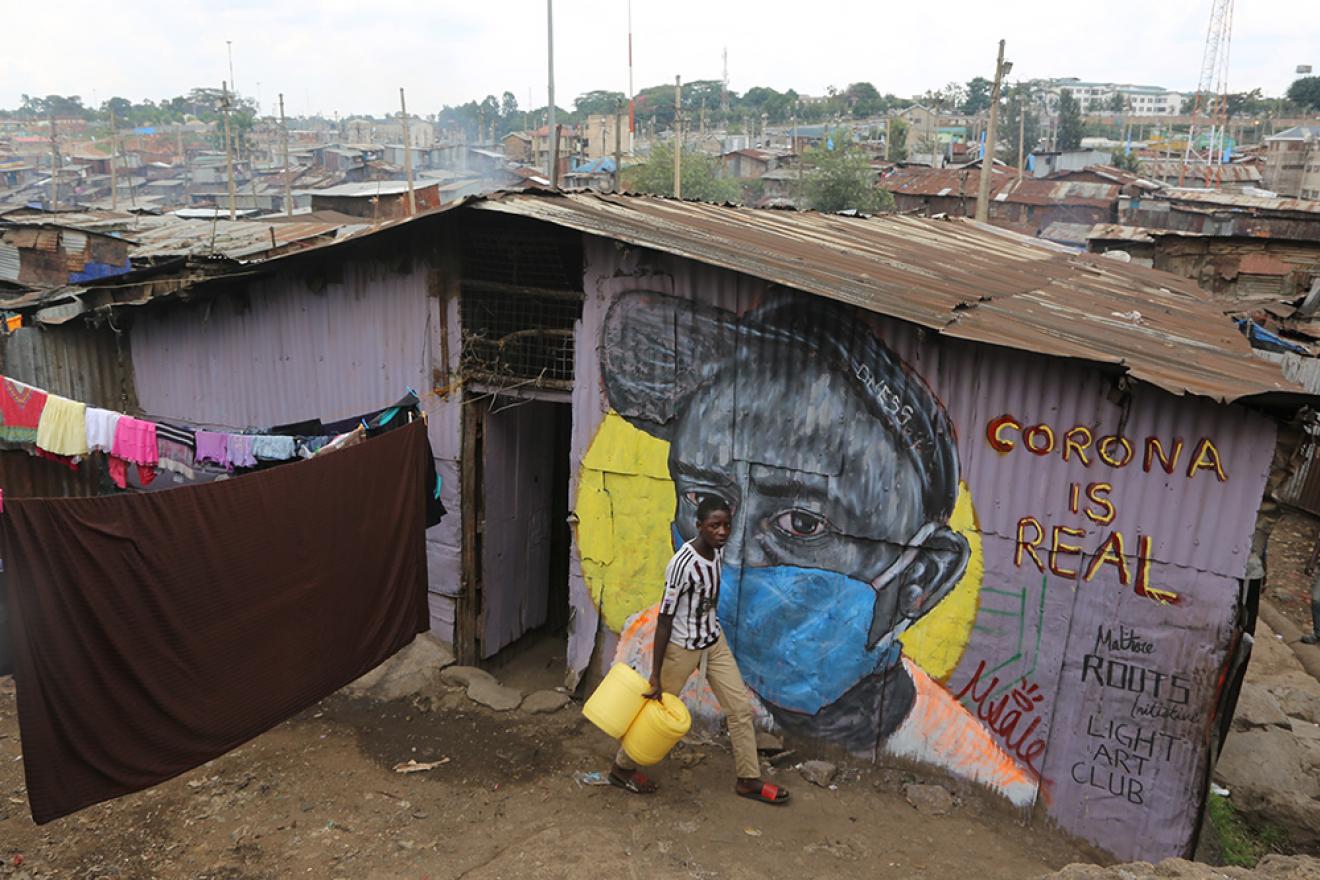

The sanitary crisis, and the massive social and economic impacts that it carries, are making visible and exacerbating pre-existing gendered, racial and class-based longstanding inequalities that have exponentially increased over the past ten years – a consequence of neoliberal policies, the privatization of public infrastructures and services, unpaid and underpaid care work and the greedy commodification of the commons. Over-exploited and impoverished Black and Latina communities are among the most affected by the lack of access to public health in the USA, the richest country on the planet. At the same time, recommendations to “stay at home and wash your hands” fail to consider the life-threatening constraints of 1.6 billion people living in inadequate housing conditions (including more than 1 billion people in so-called informal settlements and 2.2 billion lacking access to drinking water and sanitation), or the urgent needs of more than 150 million houseless women, man and children living on the streets worldwide. Overall, remote work and education is not an option for at least half of the global population relying on daily wages that, in turn, increase their fragility in facing the current deadly epidemic.

In Ahmedabad, India, street vendors are playing a crucial role in ensuring food security for all areas of the city in a collaborative initiative that has the potential for replication in cities across the country. Photo: SEWA

In the midst of amplified precarity, national and local governments from across the political spectrum are taking a cascade of measures that signal both hope and fears. Because several, well-known tensions and false dichotomies are once again present: social needs versus economic concerns; humanitarian relief versus medium/long term ‘development’; the sectorial, competitive, and divisive reaction versus the integral, collaborative, and community building approach. The role of the public sector becomes critical, but with it also the renewed risks of bureaucratic centralization, anti-democratic political agendas and crony capitalism. So let us pause for a moment and ask some important questions: Are those people in the most vulnerable conditions receiving the help they need? Are the policies being implemented reducing or widening the inequality gaps? Who are the individuals and groups not being considered? And who are the (few) ones making, once again, (a lot of) profit under pandemic conditions?

Cities as places of sorrow… and hope?

According to UN-Habitat, 95% of COVID-19 total cases are in urban areas, with more than 1,430 cities affected in 210 countries. The daunting images and figures of the death toll in New York, Milan or Guayaquil will be imprinted in our retinas for a long time, accompanied by the tragic testimonies of thousands of people that lost their loved ones within just a few weeks. The faces of desperate migrants forced to return to rural areas or countries of origin, in the midst of sudden national lockdowns and on the verge of hunger in places like India, should never be forgotten. With few exceptions, lack of coordination and even openly contradictory discourses and actions from official spheres has been the rule, with terrible consequences and millions of lives impacted.

Local governments and communities are once again the first responders, although often lacking adequate resources and in many cases confronting reluctant —and even authoritarian— national authorities. Even within limited budgets, several local and regional actors have been taking rapid and bold measures to address the current crisis . By mobilizing a wide network of in-kind support and de-commodifying access to essential goods and services, they are seeking to guarantee housing, water, food and electricity to everyone. Rent moratoriums on public housing, lifted fees, and enhanced food banks are combined with pop-up clinics and remote health attention. Repurposing of buildings, land and public space has become a critical tool. Empty housing and hotel rooms, conference centres, arenas and other community facilities are adapted to provide shelter for homeless people, women suffering domestic violence, and health care workers in need of isolation. Empty streets are being transformed in wider lines for bikers and pedestrians.

A rent strike mural in Hyde Park (Chicago) Photo: Darius Griffin

While recognizing the relevance of these fundamental and urgent steps to face the emergency situation, several voices are raising renewed concerns and additional questions. Are these measures enough? How long will they last? Could they be signalling the way forward into the deeper socio-economic and political changes that our societies so desperately need?

Right to the city and new municipalism: Local agendas for global transformation

From the squares and neighbourhoods of São Paulo, Mexico City, Santiago, New Delhi, Durban, Brooklyn, Beirut, Barcelona, Hamburg or Istanbul, to mention but a few paradigmatic examples,during the last decades multiple social movements have been confronting neoliberal urbanization and the commodification of all aspects of life. They have each found ways to experiment in developing more just, democratic, healthy and sustainable paradigms for organizing our societies. Linking local and global struggles, the several editions of the World Social Forum that started in the early 2000s were crucial arenas for peer-learning and alliance building, condensing into collective documents such as the World Charter for the Right to the City, that have become highly influential (see for example the Mexico City Charter for the Right to the City 2010 or the Constitution of Ecuador 2008). Fuelled by their opposition to austerity measures imposed in the context of the 2007-2008 financial crisis, Occupy, Indignad@s, theArab Spring and hundreds of similar mobilizations brought housing and land rights, food sovereignty, social and solidarity economy, public spaces, culture and other such commons to the center of shared agendas. An expanded conception of citizenship, not linked with nationality but with universal human rights, and highly participatory practices grounded on autonomy and self-government are today key political proposals across regions and different institutional regimes.

Building on these powerful streams and its own historic roots (see Roth and Shea, 2017; Rubio-Pueyo, 2017; Russell, 2019; Thompson, 2020), the New Municipalist movement has, as part of a wider consideration of how we democratically organise our cities, showed some concrete possibilities for recreating the local state, away from technocratic and corporatists mantras based on ‘competitiveness’, privatization and highly opaque, corrupt and un-democratic decision-making processes. In cities and towns across Argentina, Kurdistan, Spain, the UK or the USA, newly formed citizens’ independent parties and progressive platforms in local governments are openly challenging conventional, hierarchical and masculine leadership models by committing to the feminization of politics. Radicalizing democracy comes to gain a new meaning: not just addressing gender inequality and women’s institutional under-representation, but implementing policies that dismantle patriarchy and focus on everyday life and well-being for all. The re-municipalization of services and public-community partnerships are proving to be fundamental tools for advancing collectively-defined goals.

The current global pandemic is putting into focus the priorities and the urgent changes we can not keep postponing. Together with long-standing Indigenous cosmovisions like the buen vivir,and contemporary eco-feminist, anti-racist and de-colonial transformative agendas, the spreading of right to the city and new municipalist practices and narratives might help us create the future we need around an ethics of redistribution, solidarity and care.

Lorena Zárate is founding member of the Global Platform for the Right to the City and former president of the Habitat International Coalition

Photo: UNHabitat/Julius Mwelu