We know what the challenges are and we can see the solutions. It is up to us to re-invent the rules. From Monopoly to Commonspoly, communities of redistribution, solidarity, and care are changing the game.

Article by Lorena Zárate and Sophia Torres, originally published in The Nature of Cities

Playing games is a serious thing. Animals and humans learn how to relate with each other and with the world through games involving bodies and minds. Games provide a simplified way to understand complex issues, while at the same time broadening our perception of reality through multi-sensorial experiences. Playing games shapes our imagination and our ideas of what is possible. Games can help us to make sense of the world, to question it, and ― why not? ― to change it.

Conceived and popularized around the years of the Great Depression (1929-1939), Monopoly can be seen as the quintessential game of contemporary capitalist societies. Greed and cruelty are celebrated and rewarded, via the private accumulation of assets otherwise crucial for the collective wellbeing. Individuals playing the game are set to acquire as much residential space, basic infrastructure, and utilities as they can to the detriment of their opponents, charging them high rents and fees, and eventually pushing them into bankruptcy in order to win. Almost a century later, global reports of growing inequality reveal all the details about the richest 1% that make exponential profits (including during the COVID-19 pandemic) controlling almost every aspect of our lives and driving the planet into ecological collapse.

Awareness and demand are growing; it is high time to change the game. But how? Commonspoly (available for download under a Peer Production License) may hold some important answers in moving forward. Because rather than competing for critical resources and services, the goal is to collaborate to protect and enjoy them as common goods. Created in 2015, this board game was actually inspired by the original version of Monopoly, called by Elizabeth Magie, The Landlord’s Game (1904) and, in fact, intended to denounce the concentration of properties and abusive rents at the heart of socio-economic injustice. Instead of privatization, in Commonspoly players are encouraged to create and maintain public goods and common democratic management.

We all know that, in order to overcome the current multilayered crises and humanity’s existential challenges, we must put care for people and the planet at the core of narratives, practices, and policies. In the search for alternatives to exploitative patterns of production, distribution, and consumption, the commons and commoning practices are regaining momentum as a very-much-needed source of hope. A burgeoning, multidisciplinary academic field seems to be articulated with multi-sectorial and trans-scalar political experimentations in many places around the world.

Confronting invisibilization, fragmentation, and even criminalization, social movements, and civil society organizations, in alliance with progressive local and regional governments, are leading transformative actions. From housing cooperatives to the (re)municipalization of basic services, passing through collective land agreements, and shared management of natural and cultural goods, commoning practices are at the forefront of novel ways of democratic decision-making, while at the same time revaluing and giving a new meaning to traditional forms of organizing and sharing resources. At their core is a profound redistribution of material and symbolic power based on feminist, anti-racist, and anti-colonial principles and struggles.

Strongly connected with commoning, the right to the city and a renewed and strengthened municipalist agenda become now more crucial than ever. They represent at the same time a demand and a commitment to create more just, democratic, and sustainable places to live. The fulfillment of the social function of land and property; the defense of the commons (natural, urban, and cultural); the recognition and support of social and diverse economies; the radicalization of local democracy and the feminization of politics are some of the most prominent principles guiding a multitude of actions and advocacy efforts. Faced with the accelerated deterioration of the material conditions of life (human and more-than-human), growing social polarization, and (highly manipulated) loss of confidence in public institutions, the right to the city, the new municipalism, and the commons can crystallize the conditions of possibility for a new socio-spatial contract, radically renewed from the local sphere, based on proximity, and built on the rights and emancipatory dreams of its inhabitants.

What are the commons and why are they important?

Global public goods and the global commons are key components of the United Nations General Secretary vision and recommendations for the coming two critical decades. Under the framework of Our Common Agenda, national governments and the international community are called to protect and deliver on a wide range of natural and cultural domains, including the high seas, the atmosphere, and outer space, alongside health, economy, information, science, and peace. This so-called new global deal or new social contract is proposed to be anchored in human rights and focused on rebuilding trust, inclusion, and participation. It is presented as a “whole-of-society” effort, including individuals, civil society, state institutions, and the private sector. A renewed, “networked and effective” multilateralism recognizes an important role for cities.

However, from a right-to-the-city and municipalist approach, this agenda falls short. While it does acknowledge the need for recognizing the existence of common goods, it does not provide enough emphasis on the democratic arrangements under which those could be collectively managed in a coordinated way at local, national, and international levels. By such omission, this vision risks falling on an interpretation of the commons that will reproduce business as usual, without addressing power imbalances within and between these multi-stakeholder coalitions (i.e., international and national institutions vis à vis local governments; transnational corporations overriding public and social actors). Furthermore, the agenda’s understanding of the commons seems to be limited to global natural resources linked to ecosystem protection, without acknowledging the relevance and transformative character of multi-dimensional commoning practices in other fields and scales.

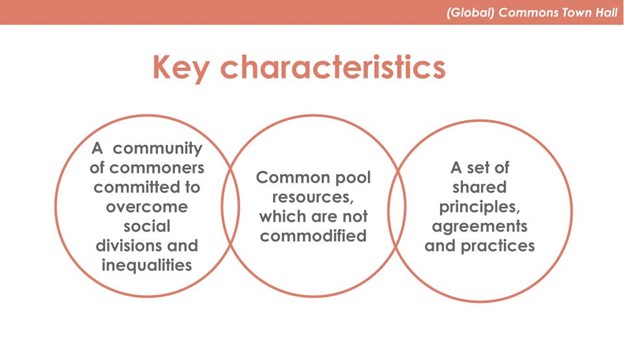

In the context of the multiple initiatives and debates that originated during the COVID-19 pandemic, local governments and civil society organizations identified commons, climate, care, and cooperation as outstanding priorities for a shared path ahead. As part of the preparatory process for the United Cities and Local Governments World Summit and Congress held in Daejeon, South Korea, in October 2022, these topics have been taken forward inside thematic Town Halls sessions and ad hoc policy papers collectively developed. The Global Platform for the Right to the City was in charge of facilitating the track on the commons[i], which came up with the following working definition: “The commons are material and immaterial goods, resources, services, and social practices considered fundamental for the reproduction of life, that therefore cannot be commodified but have to be taken care of and managed in a collective way, under democratic principles of direct participation, radical inclusion, and intersectional equity and justice, within a continuum of stewardship and commitment with past and future generations and all forms of life on Mother Earth” (GPR2C et al, Global Commons Policy Paper, UCLG Town Hall process, October 2022).

As a strategy, commoning provides a concrete tool for putting the social and environmental function over accumulation, privatization, and speculation, ensuring equal access and benefit to all, and prioritizing traditionally marginalized and discriminated against groups. At the same time, it represents a productive opportunity to experiment with new forms of public-community collaboration, given that the commons introduce not only a new approach to management and delivery of resources and services but also new models for collective governance that address power imbalances. Moreover, collective arrangements for the management of commons by public authorities and civil society are not only more equitable, since their underlying logic does not rely on profitability, but they also reinforce the ties and cooperation between public management and community spheres.

The paper incorporates references to concrete examples covering eight fundamental thematic areas: housing and land; food systems and agro-ecology; basic services (water and sanitation, energy, waste management, internet access); culture and education; knowledge, information, and digital rights; safe and accessible public spaces and livelihoods; natural resources and ecosystems. The selected cases show that ongoing efforts on the commons and commoning practices are present in cities and regions around the globe, including Brazil, Italy, Namibia, Peru, Puerto Rico, Spain, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Zimbabwe.

Moving forward: What do the commons need to flourish?

As pointed out above, the local realm is particularly fertile for the flourishing of commoning practices. In this sense, local and regional governments play a fundamental role in creating the enabling conditions in making the commons possible. In particular, they can focus on three main kinds of actions: respect and trust; protection; and realization. The first one revolves around recognizing the autonomy and specific characteristics of commoning efforts being implemented by grassroots and civil society organizations. The second one refers to providing adequate guarantees and preventing discrimination and conflicts against the commoners. The third one implies that governments provide effective and sustained support to commoning initiatives addressing structural inequalities and are committed to building feminist, anti-racist, anti-ableist, and inter-generational alternatives. Indeed, it is key to remember that promoting social engagement and collective management practices does not imply that state authorities can withdraw from their human rights commitments and obligations.

In moving forward, two sets of specific strategies are identified in order to make commoning of goods and services possible: (re)municipalization and public-community partnerships, strongly related to practices of public procurement that prioritize social and solidarity economy actors and more democratic processes. Following Kishimoto, Steinfort & Petitjean, (re)municipalization is the term used to refer to both the creation of new public services (municipalisation) and reversals from the private sector to public ownership and management (re-municipalization). A compilation published by Transnational Institute identifies 1,400 cases implemented during the past two decades in 2,400 cities from 58 countries, with clear positive impacts such as lower costs and fees, better quality, and workers’ protection. The authors emphasize that these efforts are “fueled by the aspiration of communities and local governments to reclaim democratic control over public services and local resources, in order to pursue social and environmental goals and to foster local democracy and participation”. According to their analysis, ecological sustainability, social empowerment, and increased community wealth can be all considered as direct results of initiatives dealing with topics as diverse as water, energy, housing, food, transport, waste, telecommunications, health, and social services, to name but a few.

Certainly related, but differentiated, public-community partnerships are being promoted by grassroots organizations and governments at the local level as an effective way to strengthen the social fabric and guarantee just and democratic urban rehabilitation. Bologna and Barcelona are classic examples of institutional frameworks for regulating “civil collaboration for the urban commons”. Whether in city centers or former industrial peripheries, long-term contracts give neighborhood-based associations the responsibility and resources for the collective management of green spaces, public buildings, cooperative housing, and cultural facilities. Cities like Montevideo are also experiencing new models of co-management of public-community goods and services, while at the same time implementing the social function of land (by way of preventing speculation) and advancing gender equity and racial justice. Based on these and other learnings, a multi-disciplinary group in Amsterdam has recently been promoting the creation of a Chamber of Commons to foster debate, exchange, and experimentations that can bring about social change.

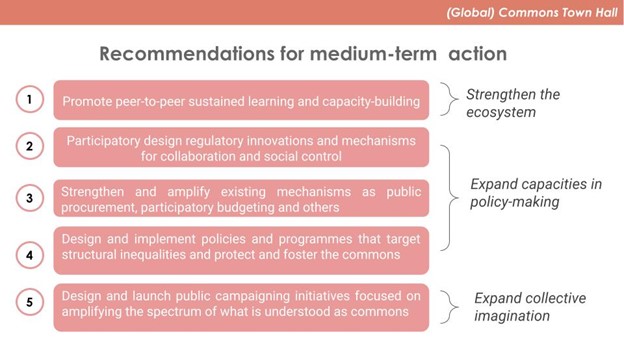

All this and more was part of the presentations and conversations held at the UCLG Commons Town Hall, where international civil society organizations and local and regional governments had the chance to further discuss the policy recommendations outlined in the paper and related next steps. These include both immediate and medium/long-term actions. Starting by identifying what already exists, the proposals focus on mobilizing available resources and capabilities, as well as building relationships and alliances. Among them are participatory mapping exercises and peer-to-peer learning; local dialogues and collaboration between municipal/regional authorities and grassroots groups; enabling regulatory frameworks; supportive public policies, programmes, and budgets; active public campaigning and engagement at international debates.

Such recommendations and the months-long collaborative effort that resulted in the policy paper have the objective to contribute to the ongoing diverse and lively debate and practices revolving around the commons, pointing towards leeways in which these can be enhanced and deepened under a stronger and sustained partnership with local authorities. As an inspiring, fun game with serious implications, Commonspoly appears to be a great tool to help create awareness and engagement from different actors and sectors, including children and youth, grassroots organizations, journalists, academics, and public officials.

By leveraging the potential of a municipalist alliance around commoning practices, the (trans)local level positions itself as a key ground place for spearheading the much-needed alternatives to respond to the ecological, socio-economic, and governance crises that define our times. We know it and we see it: it is up to us to re-invent the rules. From Monopoly to Commonspoly, communities of redistribution, solidarity, and care are changing the game.

Note:

[i] Facilitado por la Plataforma global del derecho a la ciudad, el grupo de trabajo del Cabildo Público sobre los comunes se integra de una amplia gama de organizaciones y redes, incluidas: La Coalición de Ciudades sobre derechos digitales, Fundaciones de Sociedad Abierta, el Centro Africano para la Resolución Constructiva de Controversias (ACCORD), El Fondo de las Naciones Unidas para la Infancia (UNICEF) y la Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura (FAO); así como de los/as representantes de 3 caucuses (transversales); juventud (Grupo Principal para la Infancia y Juventud), feminismo/mujeres (Comisión Huairou) y accesibilidad (World Enabled), la Asamblea General de Socios, Grupo de Colectivos de Socios para Adultos Mayores y la Unión Mundial de Ciegos). Los participantes en las múltiples sesiones de trabajo son: La Unidad de Planificación de Desarrollo de Bartlett (DPU), FIAN Internacional (FIAN), Coalición Internacional para el Habitat, Instituto internacional para el Medio Ambiente y Desarrollo (IIED), Observatori DESC (Barcelona, España), Mujeres en Empleo Informal: Globalizando y Organizando (WIEGO).