1. The Evolution of Human Rights for the Right to the City

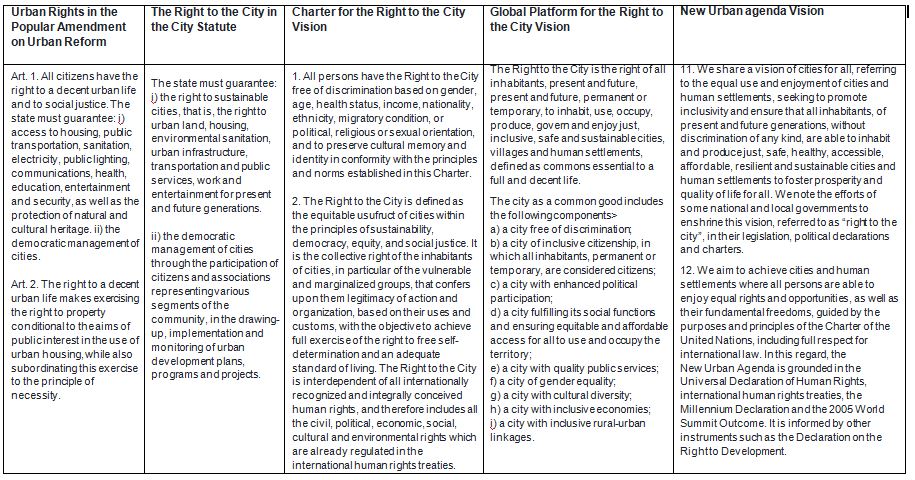

1.1. The Concept of Urban Rights in the Popular Amendment on Urban Reform

The concept of urban rights was included as a core element of the Urban Reform’s thinking which emerged during Brazil’s process of re-democratization. In particular, it was present at the National Constituent Assembly, which resulted in the Brazilian 1988 Constitution and was specifically translated into the content submitted by the historical popular amendment on urban reform of 1987.

The concept of urban rights is a human rights-based concept, one of the central issues of the political agreement that took place during the constituent process, according to which all citizens have the right to a decent urban living and to social justice. A mix of individual and collective needs and diffuse interests were put forth at the moment of defining the meaning of decent urban living. It is the state’s responsibility to guarantee housing, public transportation, sanitation, electricity, public lighting, communications, health, education, entertainment and security. Moreover, in view of diffuse interests, the state must also guarantee the protection of natural and cultural heritage and the democratic management of cities.

The concept of urban rights was linked clearly to complying with the social function of property. The right to a decent urban living was expected to make exercising the right to property conditional to the aims of public interest in the use of urban housing, while also subordinating this exercise to the principle of necessity. This principle anticipates a conflict between holders of legal and legitimate interests given that one of these interests can lawfully perish for the other one to survive. This applies particularly to the cases in which there is a conflict between housing and property, and in which the former should prevail over the latter given the pressing needs of people who do not have a decent place to live.

This concept of urban rights was a landmark in the fight for urban reform and in the political processes that took place in several states and municipalities during the creation of their state constitution, organic laws and city Master Plan during the 1990s. Under the framework of designing the City Statute, it contributed to the country’s vision of the Right to the City.

1.2. The Concept of the Right to the City in the City Statute

The drawing up of the City Statute in the National Congress spanned over more than a decade (1989-2001) due to the action of conservative parties, which were reluctant to give support to the implementation of an urban policy aimed at the full development of the social functions of property and the city. During that period, fundamental debates and formulations on the links between human rights, the environment and sustainability took place under the framework of the UN Conference on Environment and Development (Rio de Janeiro, 1992), the Human Settlements – Habitat II (Istanbul, 1996) and the National Conference of Cities (Brasilia, Chamber of Deputies, 1999). In addition, several experiences involving participatory municipal management carried out in several Brazilian cities by democratic and popular governments were important in conveying the transition from urban rights to the Right to the City adopted in the City Statute.

Since then, this Right is qualified as the right to sustainable cities, embedding the dimension of sustainability as a goal to be achieved within an urban policy that guarantees its practice. It is composed by the following elements: urban land, housing, environmental sanitation, urban infrastructure, transportation and public services, work and entertainment. The elements linked to decent urban living, which come from the vision of urban rights, prevail in this vision of the Right to the City.

The democratic management of cities – provided by Article 2, Section II of the City Statute – is another element of this right, included through a comprehensive interpretation of the urban policy guidelines defined under this law.

In regards to the question of who is considered to be entitled to the right to sustainable cities, it keeps with what is established in the right to a clean environment, in which those entitled are present and future generations.

The City Statute was the first national legislation to incorporate the Right to the City into the legal and institutional dimensions and, therefore, the understanding of this right was a source of inspiration in the subsequent process aimed at taking this right to an international level. This process was deployed in the privileged settings of the World Social Forums held in the Brazilian city of Porto Alegre in the beginning of 2000s.

2. Issues for a National and International Vision of the Right to the City

Several issues must be dealt with in depth in order to strengthen the vision of the Right to the City in Brazil and build up a global vision that would allow taking this right to the international level.

What is the definition of “city” when talking about the Right to the City? To acquire this understanding we must take into account the following elements: territory (urban and rural), the typologies of cities, size and population density, and the institutional organization (political and administrative) of cities. In Brazil, for example, there exists a huge legal restriction on how cities are understood. Cities are defined as the seat of the municipal administration according to Article 3 of the Decree-Law 311 of 1938: the seat of the municipal administration receives the category of city and gives name to it.

Who are the people to be recognized as holders of this Right to the City, taking into account the following aspects: generation, nationality, diversity of people living, working and enjoying the cities and time of residence or permanence in the city?

What category does the Right to the City have within the sphere of human rights – individual, collective or diffuse?

How can people exercise their Right to the City and with what purpose?

What should the legally protected object or asset be within the Right to the City? As happens in Brazil, several cities in different countries have been declared historical or cultural heritage and this provides legal and judicial protection to preserve their memory and identity.

3. The Evolution of the International Concept of the Right to the City

3.1. The Vision of the World Charter on the Right to the City

These questions have guided the construction of the vision of the Right to the City at an international level. They were relevant in the construction of the vision that was included in the World Charter on the Right to the City, which was developed in spaces of debate and articulation on urban issues such as the World Social Forum. They also influenced the vision of the Global Platform on the Right to the City and the New Urban Agenda endorsed by the UN Conference Habitat III (Quito, 2016).

The World Charter on the Right to the City defines this right as the equal enjoyment of cities while respecting the principles of sustainability, democracy, equity and social justice. As for how it is classified within the sphere of human rights, it is defined as a collective right of all city inhabitants, especially those vulnerable and disfavoured. Therefore this right confers them legitimacy of action and organisation in accordance with their usages and customs.

There is a positive development in the World Charter on the Right to the City insofar as it acknowledges as elements of this right cities without any form of discrimination and cities that preserve their history and cultural identity. Regarding the territorial scope in which this right can be exercised, it covers the city territory and its rural surroundings.

In the Charter, the concept of city has two meanings. On one hand, given its physical character it is any town, village, city, capital, locality, suburb, settlement or similar which is institutionally organised as a local unit of Municipal or Metropolitan Government. It includes both the urban and the rural and semi-rural portions of its territory. As a political space, the city is the set of institutions and actors which take part in its management such as governmental, legislative and judicial authorities; institutionalized social participation agencies, social organizations and movements, and the community in general.

As for the question of who is entitled to this right, citizens are all persons who live in the city either permanently or temporarily.

3.2. The Vision of the Global Platform for the Right to the City

The Global Platform for the Right to the City is a global network made up of international civil society networks and organizations, and local governments. The platform collectively promoted a series of mobilizations and coordination during the UN Conference Habitat III process in order to include the vision of the Right to the City in the New Urban Agenda.

According to the platform’s vision, the Right to the City is by nature a collective and diffuse human right combined with the social functions and democratic management of cities, which allows integrating all human rights in a specific territory based on international standards for the protection of human rights.

Regarding who is entitled to the Right to the City, it is the right of all inhabitants, present and future. Moreover, it also adopts the World Charter’s vision of citizen which covers both permanent and temporary inhabitants.

The way of exercising the Right to the City is by occupying, using and producing cities. The objective is to have fair, inclusive and sustainable cities. The city is defined as a common good, essential to a full and decent life. This includes the following elements:

a) a city free of discrimination;

b) a city of inclusive citizenship, which recognizes all inhabitants who live temporarily and permanently in the city as citizens;

c) a city with enhanced political participation;

d) a city fulfilling its social functions, that is, ensuring equitable access of use and occupation of spaces;

e) a city with quality public spaces;

f) a city of gender equality;

g) a city with cultural diversity;

h) a city with inclusive economies;

i) a city as a common settlement system and ecosystem which respects rural-urban linkages.

According to this vision, the city as a common good is an asset which must be legally and judicially protected through the Right to the City.

3.3. The Vision of the New Urban Agenda

The New Urban Agenda largely takes on the vision advocated by the Global Platform. Paragraph 11 of the New Urban Agenda considers the holders of this right “all inhabitants of present and future generations, without discrimination of any kind”. Therefore, this can be interpreted as the recognition as well of temporary dwellers.

As for the territorial scope of this right, it includes all human settlements. Regarding the way of exercising it, the document considers the right to inhabit and produce cities and human settlements which are just, safe, healthy, resilient and sustainable.

Paragraph 13 of the New Urban Agenda takes into account the following elements of the Right to the City: cities without discrimination of any kind, with a social function, gender equality, public spaces, inclusive economy and the protection of ecosystems.

This new vision brings about a new meaning to human rights and to the functions and ways of life in our cities and human settlements. It must be strengthened and strategically considered by countries and cities in their fight against social, economic, cultural and territorial inequalities, and the impacts of global warming and climate change.

4. Emerging Question to Help Strengthen the Vision of the Right to the City in Brazil

Several questions should be delved into in order to consolidate the vision of the Right to the City in our country, but the baseline should be the understanding of the city as a common good, as the emerging pillar of the Right to the City. This brings about other visions and ideas which can contribute to our goal, such as the right to the “buen vivir” (the good living), native to the indigenous civilizations of Latin America.

Please find the conclusions of this article in the table below

* Click here to download the article.

* Click here to download the article.

Article by Nelson Saule, coordinator of the Right to the City Area in Polis Institute of Studies, Coordinator of the Support Group of the Global Platform for the Right to the City, and Coordinator of International Relationships in the Instituto Brasileño de Derecho Urbanístico.